Rutgers engineers have developed a breakthrough device that can significantly reduce the cost of sophisticated lab tests for medical disorders and diseases, such as HIV, Lyme disease and syphilis.

The new device uses miniaturized channels and valves to replace “benchtop” assays – tests that require large samples of blood or other fluids and expensive chemicals that lab technicians manually mix in trays of tubes or plastic plates with cup-like depressions.

“The main advantage is cost – these assays are done in labs and clinics everywhere,” said Mehdi Ghodbane, who earned his doctorate in biomedical engineering at Rutgers and now works in biopharmaceutical research and development at GlaxoSmithKline.

Rutgers engineers have developed a breakthrough device that can significantly reduce the cost of sophisticated lab tests for medical disorders and diseases, such as HIV, Lyme disease and syphilis.

The new device uses miniaturized channels and valves to replace “benchtop” assays – tests that require large samples of blood or other fluids and expensive chemicals that lab technicians manually mix in trays of tubes or plastic plates with cup-like depressions.

“The main advantage is cost – these assays are done in labs and clinics everywhere,” said Mehdi Ghodbane, who earned his doctorate in biomedical engineering at Rutgers and now works in biopharmaceutical research and development at GlaxoSmithKline.

Ghodbane and six Rutgers researchers recently published their results in the Royal Society of Chemistry’s journal, Lab on a Chip.

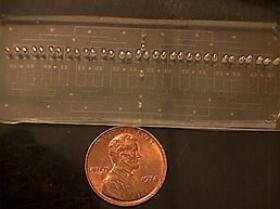

The Rutgers lab-on-a chip is three inches long and an inch wide - the size of a glass microscope slide.

The lab-on-chip device, which employs microfluidics technology, along with making tests more affordable for patients and researchers, opens doors for new research because of its capability to perform complex analyses using 90 percent less sample fluid than needed in conventional tests.

“A great deal of research has been hindered because in many cases one is not able to extract enough fluid,” Ghodbane said.

The Rutgers breakthrough also requires one-tenth of the chemicals used in a conventional multiplex immunoassay, which can cost as much as $1500. Additionally, the device automates much of the skilled labor involved in performing tests.

“The results are as sensitive and accurate as the standard benchtop assay,’’ said Martin Yarmush, the Paul and Mary Monroe Chair and Distinguished Professor of biomedical engineering at Rutgers and Ghodbane’s adviser.

Until now, animal research on central nervous system disorders, such as spinal cord injury and Parkinson’s disease, has been limited because researchers could not extract sufficient cerebrospinal fluid to perform conventional assays.

“With our technology, researchers will be able to perform large-scale controlled studies with comparable accuracy to conventional assays,” Yarmush said.

The discovery could also lead to more comprehensive research on autoimmune joint diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis through animal studies. As with spinal fluid, the amount of joint fluid, or synovial fluid, researchers are able to collect from lab animals is minuscule.

Photo: Courtesy Mehdi Ghodbane: The Rutgers lab-on-a chip is three inches long and an inch wide - the size of a glass microscope slide.

Read more at Rutgers University.