Iron screws and other so-called ferromagnetic materials are made up of atoms with electrons that act like little magnets.

Iron screws and other so-called ferromagnetic materials are made up of atoms with electrons that act like little magnets. Normally, the orientations of the magnets are aligned within one region of the material but are not aligned from one region to the next. Think of groups of tourists in Times Square pointing to different billboards all around them. But when a magnetic field is applied, the orientations of the magnets, or spins, in the different regions line up and the material becomes fully magnetized. This would be like the packs of tourists all turning to point at the same sign.

The process of spins lining up, however, does not happen all at once. Rather, when the magnetic field is applied, different regions, or so-called domains, influence others nearby, and the changes spread across the material in a clumpy fashion. Scientists often compare this effect to an avalanche of snow, where one small lump of snow starts falling, pushing on other nearby lumps, until the entire mountainside of snow is tumbling down in the same direction.

This avalanche effect was first demonstrated in magnets by the physicist Heinrich Barkhausen in 1919. By wrapping a coil around a magnetic material and attaching it to a loudspeaker, he showed that these jumps in magnetism can be heard as a crackling sound, known today as Barkhausen noise.

Read more at: California Institute of Technology

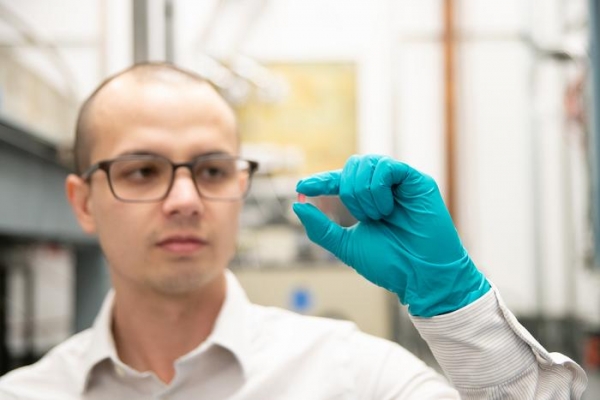

Chistopher Simon holds a crystal of lithium holmium yttrium fluoride. (Photo Credit: Lance Hayashida/Caltech)