Like the waistband of a couch potato in midlife, the orbits of planets in our solar system are expanding. It happens because the Sun’s gravitational grip gradually weakens as our star ages and loses mass. Now, a team of NASA and MIT scientists has indirectly measured this mass loss and other solar parameters by looking at changes in Mercury’s orbit.

Like the waistband of a couch potato in midlife, the orbits of planets in our solar system are expanding. It happens because the Sun’s gravitational grip gradually weakens as our star ages and loses mass. Now, a team of NASA and MIT scientists has indirectly measured this mass loss and other solar parameters by looking at changes in Mercury’s orbit.

The new values improve upon earlier predictions by reducing the amount of uncertainty. That’s especially important for the rate of solar mass loss, because it’s related to the stability of G, the gravitational constant. Although G is considered a fixed number, whether it’s really constant is still a fundamental question in physics.

“Mercury is the perfect test object for these experiments because it is so sensitive to the gravitational effect and activity of the Sun,” said Antonio Genova, the lead author of the study published in Nature Communications and a Massachusetts Institute of Technology researcher working at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The study began by improving Mercury’s charted ephemeris — the road map of the planet’s position in our sky over time. For that, the team drew on radio tracking data that monitored the location of NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft while the mission was active. Short for Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry, and Ranging, the robotic spacecraft made three flybys of Mercury in 2008 and 2009 and orbited the planet from March 2011 through April 2015. The scientists worked backward, analyzing subtle changes in Mercury’s motion as a way of learning about the Sun and how its physical parameters influence the planet’s orbit.

Read more at NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

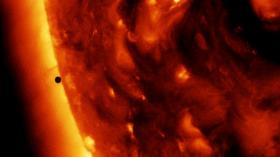

Image: Mercury's proximity to the Sun and small size make it exquisitely sensitive to the dynamics of the Sun and its gravitational pull. (Credit: NASA/SDO)