“The current methods of restoring these sites are not as cost efficient or energy efficient as they could be, and can cause more environmental disruption,” said Susan Kaminskyj, a professor in the Department of Biology. “Our biotech innovation should help to solve this type of problem faster and with less additional disturbance.”

Kaminskyj led a research team that included three biology students and a post-doctoral fellow in the U of S College of Arts and Science. Results from their work, funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, were published in the journal PLOS ONE.

“The current methods of restoring these sites are not as cost efficient or energy efficient as they could be, and can cause more environmental disruption,” said Susan Kaminskyj, a professor in the Department of Biology. “Our biotech innovation should help to solve this type of problem faster and with less additional disturbance.”

Kaminskyj led a research team that included three biology students and a post-doctoral fellow in the U of S College of Arts and Science. Results from their work, funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, were published in the journal PLOS ONE.

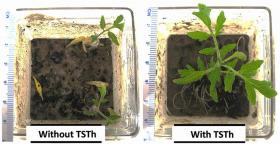

About 800 square kilometers of Alberta’s Athabasca oilsands are covered in coarse tailings: some of the leftover materials from refining surface-mined bitumen. Contaminated with an oily residue, lacking nutrients and resistant to absorbing water, coarse tailings are a hostile environment to both plants and soil microbes.

But after tailings lie exposed for a decade or so, a few weedy plants often manage to take root. One of these, a dandelion, was obtained by the U of S team in 2007 upon being discovered growing naturally on a coarse tailings site. From its roots, former graduate student Xiaohui Bao isolated a unique strain of fungus.

Continue reading at University of Saskatchewan.

Photo via University of Saskatchewan.