On New Year’s Day, 1909, a grocer named Julius Fried and his novice drilling crew, the Lakeview Oil Company, spudded a well in the desert valley scrub in the Midway-Sunset oil field, 110 miles north of Los Angeles. For the first 1,655 feet, the well yielded only dust, and then Lakeview ran out of money.

On New Year’s Day, 1909, a grocer named Julius Fried and his novice drilling crew, the Lakeview Oil Company, spudded a well in the desert valley scrub in the Midway-Sunset oil field, 110 miles north of Los Angeles. For the first 1,655 feet, the well yielded only dust, and then Lakeview ran out of money.

Fried must have gone to his grave wishing his crew had held on just a little longer. On March 14, 1910, the Union Oil Company’s Charlie Woods — nicknamed “Dry Hole Charlie” for his long streak of dusters — struck what he would later describe as an “artery in the earth’s great storehouse of oil.” When his drill bit reached 2,225 feet beneath the surface, Lakeview No. 1 sent up a sudden column of pressurized oil 200 feet into the air. For 544 days, the Lakeview Gusher would defy every effort to contain it, eventually spreading 9.4 million barrels of oil across the valley floor. Less than half of it was recovered. It remains, to this day, the largest oil spill in the history of the world.

Read more at Yale Environment 360

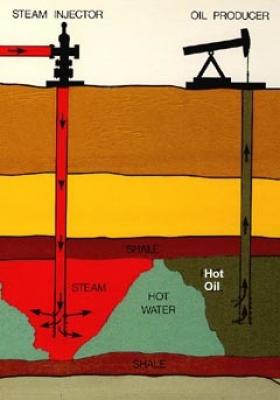

Image: Steam is pumped underground to warm and loosen thick crude oil, so it can flow to the surface.

Image Credit: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY