Since Captain James Cook’s discovery in the 1770s that water encompassed the Earth’s southern latitudes, oceanographers have been studying the Southern Ocean, its physics, and how it interacts with global water circulation and the climate.

Since Captain James Cook’s discovery in the 1770s that water encompassed the Earth’s southern latitudes, oceanographers have been studying the Southern Ocean, its physics, and how it interacts with global water circulation and the climate.

Through observations and modeling, scientists have long known that large, deep currents in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans flow southward, converging on Antarctica. After entering the Southern Ocean they overturn — bringing water up from the deeper ocean — before moving back northward at the surface. This overturning completes the global circulation loop, which is important for the oceanic uptake of carbon and heat, the resupply of nutrients for use in biological production, as well as the understanding of how ice shelves melt.

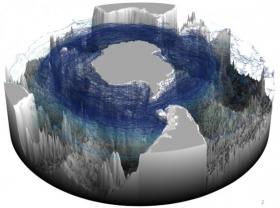

Yet the three-dimensional structure of the pathways that these water particles take to reach the Southern Ocean’s surface mixed layer and their associated timescales was poorly understood until recently. Now researchers have found that deep, relatively-warm water from the three ocean basins enters the Southern Ocean and spirals southeastwards and upwards around Antarctica before reaching the ocean’s mixed layer, where it interacts with the atmosphere.

Continue reading at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Image: This model illustrates the three-dimensional upward spiral of North Atlantic deep water through the Southern Ocean. Image courtesy of the researchers.