Checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy has been shown to be very effective in recurrent and metastatic head and neck cancer but only in a minority of patients. University of California San Diego School of Medicine researchers may have found a way to double down on immunotherapy’s effectiveness.

Checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy has been shown to be very effective in recurrent and metastatic head and neck cancer but only in a minority of patients. University of California San Diego School of Medicine researchers may have found a way to double down on immunotherapy’s effectiveness.

In a paper published in the journal JCI Insights on September 21, researchers report that a combination of toll-like receptors (TLR) agonists — specialized proteins that initiate immune response to foreign pathogens or, in this case, cancer cells — and other immunotherapies injected directly into a tumor suppresses tumor growth throughout the whole body.

“The mechanism reverses the phenotype of a tumor by changing its inherit properties to make the tumor more immunogenic,” said Ezra E.W. Cohen, MD, professor of medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine and associate director for translational science at UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center and senior author on the paper. “In this study, the combination of immunotherapy drugs resulted in the complete elimination of cancer cells and even when re-challenged the tumors did not recur.”

Macrophages are specialized immune cells that destroy targeted cells. They are supposed to present antigens to the immune system to get it started, but in cancer they stop doing that so the immune system is unable to recognize the cancer. The combination of drugs restored the ability of macrophages to initiate a tumor response and allow the immune system to eliminate the cancer.

Read more at University of California - San Diego

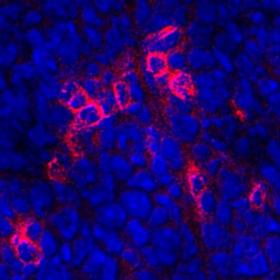

Image: The combination therapy with TLR agonist and anti-PD-1 agent activates CD8+ T cells (red) in the tumors. (Credit: UC San Diego Health)