Antarctic researchers from Rice University have discovered one of nature’s supreme ironies: On Earth’s driest, coldest continent, where surface water rarely exists, flowing liquid water below the ice appears to play a pivotal role in determining the fate of Antarctic ice streams.

The finding, which appears online this week in Nature Geoscience, follows a two-year analysis of sediment cores and precise seafloor maps covering 2,700 square miles of the western Ross Sea. As recently as 15,000 years ago, the area was covered by thick ice that later retreated hundreds of miles inland to its current location. The maps, which were created from state-of-the-art sonar data collected by the National Science Foundation research vessel Nathaniel B. Palmer, revealed how the ice retreated during a period of global warming after Earth’s last ice age. In several places, the maps show ancient water courses — not just a river system, but also the subglacial lakes that fed it.

Hidden river once flowed beneath Antarctic ice

Antarctic researchers from Rice University have discovered one of nature’s supreme ironies: On Earth’s driest, coldest continent, where surface water rarely exists, flowing liquid water below the ice appears to play a pivotal role in determining the fate of Antarctic ice streams.

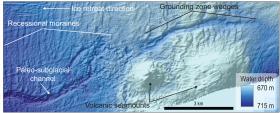

The finding, which appears online this week in Nature Geoscience, follows a two-year analysis of sediment cores and precise seafloor maps covering 2,700 square miles of the western Ross Sea. As recently as 15,000 years ago, the area was covered by thick ice that later retreated hundreds of miles inland to its current location. The maps, which were created from state-of-the-art sonar data collected by the National Science Foundation research vessel Nathaniel B. Palmer, revealed how the ice retreated during a period of global warming after Earth’s last ice age. In several places, the maps show ancient water courses — not just a river system, but also the subglacial lakes that fed it.

Today, Antarctica is covered by ice that is in some places more than 2 miles thick. Though deep, the ice is not static. Gravity compresses the ice, and it moves under its own weight, creating rivers of ice that flow to the sea. Even with the best modern instruments, the undersides of these massive ice streams are rarely accessible to direct observation.

Read more at Rice University

Image: An example of seafloor bathymetry data that Rice University oceanographers used to identify a paleo-subglacial channel, grounding line landforms, volcanic seamounts and other features used in their study. (Image courtesy of L. Simkins / Rice University)