Since causing major outbreaks in Saudi Arabia in 2014, and in Korea a year later, the virus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome is laying low. But by no means has it disappeared: A recent cluster of 34 cases cropped up in July in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia’s capital. The dromedary camels who harbored the virus for more than 20 years aren’t going anywhere, and neither is MERS.

Since causing major outbreaks in Saudi Arabia in 2014, and in Korea a year later, the virus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome is laying low. But by no means has it disappeared: A recent cluster of 34 cases cropped up in July in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia’s capital. The dromedary camels who harbored the virus for more than 20 years aren’t going anywhere, and neither is MERS.

But for many researchers, now—between major outbreaks—is the perfect time to develop treatments and vaccines for a virus that kills a third of the people it infects. The initial stigma of MERS, much like SARS, has made it difficult to study the survivors whose blood carries valuable information about virus-fighting strategies. But in a downturn, more survivors have agreed to donate blood samples—21 of whom contributed to a paper published Friday in Science Immunology.

That might not seem like a lot, but only 2,040 MERS cases have ever been diagnosed and reported, in part because the starting symptoms—coughing, fever, trouble breathing—are so general. “So obtaining the specimens that we did amounted to something like 2 to 3 percent of the total [known] survivors of MERS,” says Stanley Perlman, a microbiologist at the University of Iowa and a coauthor of the study.

Read more at Wired

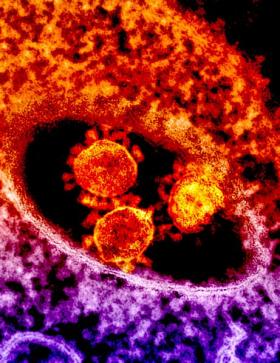

Photo credit: NIAID via Wikimedia Commons