We may be capable of finding microbes in space—but if we did, could we tell what they were, and that they were alive?

We may be capable of finding microbes in space—but if we did, could we tell what they were, and that they were alive?

This month the journal Astrobiology is publishing a special issue dedicated to the search for signs of life on Saturn's icy moon Enceladus. Included is a paper from Caltech's Jay Nadeau and colleagues offering evidence that a technique called digital holographic microscopy, which uses lasers to record 3-D images, may be our best bet for spotting extraterrestrial microbes.

No probe since NASA's Viking program in the late 1970s has explicitly searched for extraterrestrial life—that is, for actual living organisms. Rather, the focus has been on finding water. Enceladus has a lot of water—an ocean's worth, hidden beneath an icy shell that coats the entire surface. But even if life does exist there in some microbial fashion, the difficulty for scientists on Earth is identifying those microbes from 790 million miles away.

"It's harder to distinguish between a microbe and a speck of dust than you'd think," says Nadeau, research professor of medical engineering and aerospace in the Division of Engineering and Applied Science. "You have to differentiate between Brownian motion, which is the random motion of matter, and the intentional, self-directed motion of a living organism."

Read more at California Institute of Technology

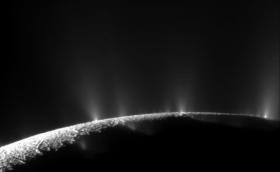

Image: Plumes water ice and vapor spray from many locations near the south pole of Saturn's moon Enceladus, as documented by the Cassini-Huygens mission. (Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute)