In some places, water is dangerously scarce. In the African Sahel, generations of severe droughts have claimed millions of lives and have turned fertile pastures into swaths of desert. In Brazil, residents of the water-starved city of São Paulo have been frenetically digging homemade wells to mine fresh water, while schoolkids skip brushing their teeth as a conservation measure. And in California, devastating drought conditions in recent years idled nearly a half-million acres of crops and triggered the loss of tens of thousands of jobs.

In some places, water is dangerously scarce. In the African Sahel, generations of severe droughts have claimed millions of lives and have turned fertile pastures into swaths of desert. In Brazil, residents of the water-starved city of São Paulo have been frenetically digging homemade wells to mine fresh water, while schoolkids skip brushing their teeth as a conservation measure. And in California, devastating drought conditions in recent years idled nearly a half-million acres of crops and triggered the loss of tens of thousands of jobs.

As areas of the planet dry up, scientists are hunting for new sources of fresh water. And they’re finding it in places many people wouldn’t expect: under the ocean. By some estimates, nearly 120,000 cubic miles of fresh water lies buried beneath the seafloor—more water than the sun evaporates from the Earth’s surface each year.

These subsea reservoirs could someday be tapped like vast offshore wells to provide additional freshwater resources to an increasingly water-scarce planet, say Rob Evans and Dan Lizarralde, scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Continue reading at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

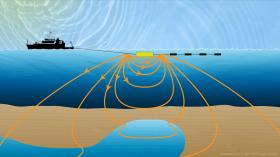

Image: Using a new method to distinguish fresh water from oil or salt water, scientists are exploring beneath the continental shelf off New England to look for large pockets of trapped fresh water. This water may be continually filling from groundwater flowing from land or, alternatively, may have been left behind by ice-age glaciers. (Eric S. Taylor, WHOI Graphic Services)