In the first such continent-wide survey, scientists have found extensive drainages of meltwater flowing over parts of Antarctica’s ice during the brief summer. Researchers already knew such features existed, but assumed they were confined mainly to Antarctica’s fastest-warming, most northerly reaches. Many of the newly mapped drainages are not new, but the fact they exist at all is significant; they appear to proliferate with small upswings in temperature, so warming projected for this century could quickly magnify their influence on sea level. An accompanying study looks at how such systems might influence the great ice shelves ringing the continent, which some researchers fear could collapse, bringing catastrophic sea-level rises. Both studies appear this week in the leading scientific journal Nature.

In the first such continent-wide survey, scientists have found extensive drainages of meltwater flowing over parts of Antarctica’s ice during the brief summer. Researchers already knew such features existed, but assumed they were confined mainly to Antarctica’s fastest-warming, most northerly reaches. Many of the newly mapped drainages are not new, but the fact they exist at all is significant; they appear to proliferate with small upswings in temperature, so warming projected for this century could quickly magnify their influence on sea level. An accompanying study looks at how such systems might influence the great ice shelves ringing the continent, which some researchers fear could collapse, bringing catastrophic sea-level rises. Both studies appear this week in the leading scientific journal Nature.

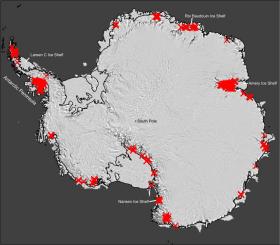

Explorers and scientists have documented a few Antarctic melt streams starting in the early 20th century, but no one knew how extensive they were. The authors found out by systematically cataloging images of surface water in photos taken from military aircraft from 1947 onward, and satellite imagery from 1973 on. They found nearly 700 seasonal systems of interconnected ponds, channels and braided streams fringing the continent on all sides. Some run as far as 75 miles, with ponds up to several miles wide. They start as close as 375 miles from the South Pole, and at 4,300 feet above sea level, where liquid water was generally thought to be rare to impossible.

Read more at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory - Columbia University

Image adapted from Kingslake et al., Nature 2017