Important microscopic creatures which produce half of the oxygen in the atmosphere can rapidly adapt to global warming, new research suggests.

Phytoplankton, which also act as an essential food supply for fish, can increase the rate at which they take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen while in warmer water temperatures, a long-running experiment shows.

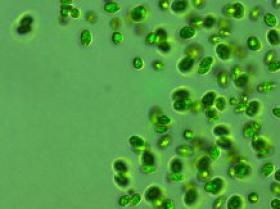

Monitoring of one species, a green algae, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, after ten years of them being in waters of a higher temperature shows they quickly adapt so they are still able to photosynthesise more than they respire.

Important microscopic creatures which produce half of the oxygen in the atmosphere can rapidly adapt to global warming, new research suggests.

Phytoplankton, which also act as an essential food supply for fish, can increase the rate at which they take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen while in warmer water temperatures, a long-running experiment shows.

Monitoring of one species, a green algae, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, after ten years of them being in waters of a higher temperature shows they quickly adapt so they are still able to photosynthesise more than they respire.

Phytoplankton use chlorophyll to capture sunlight, and photosynthesis to turn it into chemical energy. This means they are critical for reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and for providing food for aquatic life. It is crucial to know how these tiny organisms – which are not visible to the naked eye – react to climate change in the long-term. Experts had made predictions that that climate change would have negative effects on phytoplankton. But a new study shows green algae can adjust to warmer water temperatures. They become more competitive and increase the amount they are able to photosynthesise.

Read more at University of Exeter

Image: Phytoplankton can increase the rate at which they take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen while in warmer water temperatures.

Image Credits: University of Exeter