The oceans are great at absorbing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air, but when their deep waters are brought to the surface, the oceans themselves can be a source of this prevalent greenhouse gas.

Wind patterns together with the Earth’s rotation drive deep ocean water — and the CO2 it sequesters — upward, replacing surface water moving offshore. A process known as upwelling, it occurs on the west coasts of continents. And it’s part of a never-ending loop in which CO2 levels in the surface ocean rise and fall in a natural rhythm.

The oceans are great at absorbing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air, but when their deep waters are brought to the surface, the oceans themselves can be a source of this prevalent greenhouse gas.

Wind patterns together with the Earth’s rotation drive deep ocean water — and the CO2 it sequesters — upward, replacing surface water moving offshore. A process known as upwelling, it occurs on the west coasts of continents. And it’s part of a never-ending loop in which CO2 levels in the surface ocean rise and fall in a natural rhythm.

But when CO2 levels rise, ocean pH falls, causing ocean acidification. Seeking to explore how short-term periods of elevated CO2 from upwelling impact the bacteria in the water, UC Santa Barbara researchers found that the additional CO2 — and corresponding drop in pH — increased the respiration of these organisms. This means more resources are recycled rather than retained in the food web. The results appear in the journal PLOS ONE.

Continue reading at the University of California - Santa Barbara

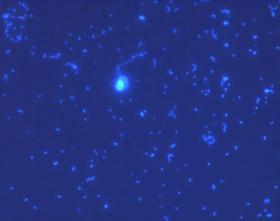

Photo: Bacterioplankton (dots) surrounded by a nanoflagellate (white), which preys on the bacteria.

Photo Credits: Rachel Parsons