Nearly a century ago, German chemist Fritz Haber won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for a process to generate ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen gases. The process, still in use today, ushered in a revolution in agriculture, but now consumes around one percent of the world’s energy to achieve the high pressures and temperatures that drive the chemical reactions to produce ammonia.

Today, University of Utah chemists publish a different method, using enzymes derived from nature, that generates ammonia at room temperature. As a bonus, the reaction generates a small electrical current. The method is published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

Nearly a century ago, German chemist Fritz Haber won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for a process to generate ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen gases. The process, still in use today, ushered in a revolution in agriculture, but now consumes around one percent of the world’s energy to achieve the high pressures and temperatures that drive the chemical reactions to produce ammonia.

Today, University of Utah chemists publish a different method, using enzymes derived from nature, that generates ammonia at room temperature. As a bonus, the reaction generates a small electrical current. The method is published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

Although chemistry and materials science and engineering professor Shelley Minteer and postdoctoral scholar Ross Milton have only been able to produce small quantities of ammonia so far, their method could lead to a less energy-intensive source of the ammonia, used worldwide as a vital fertilizer.

“It’s a spontaneous process, so rather than having to put energy in, it’s actually generating its own electricity,” Minteer says.

Continue reading at University of Utah

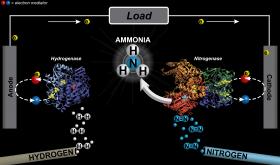

Image: A diagram of the chemistry used in a hydrogenase-nitrogenase ammonia producing fuel cell.

Photo credit: Ross Milton