By the year 2100, sea levels might rise as much as 2.5 meters above their current levels, which would seriously threaten coastal cities and other low-lying areas. In turn, this would force animals to migrate farther inland in search of higher ground. But accelerated urbanization, such as the rapidly expanding Piedmont area that stretches from Atlanta to eastern North Carolina, could cut off their escape routes and create climate-induced extinctions.

By the year 2100, sea levels might rise as much as 2.5 meters above their current levels, which would seriously threaten coastal cities and other low-lying areas. In turn, this would force animals to migrate farther inland in search of higher ground. But accelerated urbanization, such as the rapidly expanding Piedmont area that stretches from Atlanta to eastern North Carolina, could cut off their escape routes and create climate-induced extinctions.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to combine these multiple threats to predict how future land-use change and aspects of climate change, such as sea-level rise, are interactively altering the landscape connectivity picture for multiple species,” said Leonard, a postdoctoral scientist at Clemson University. “In our models, we focused on six different species — black bear, red wolf, Eastern cougar, Eastern diamondback rattlesnake, timber rattlesnake and pine snake — and grouped them based on the way they move around the landscape. We then looked at how increased urbanization and sea-level rise would work together to change the picture of connectivity in the future.”

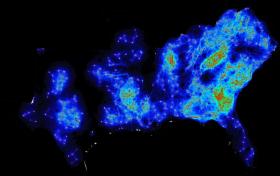

Much of the manuscript is based on data produced by high-resolution connectivity maps that were designed at Clemson University. These maps were paired with satellite imagery to display the potential corridors used by animal populations to move between both large and small areas. Also, more than 60 highly regarded biologists provided additional data by sharing their accumulated expertise, completing surveys and answering follow-up questions. The manuscript emphasizes that using corridors to reconnect fragments of natural habitat is essential for promoting the survival of many species. It further states that present and future threats to biodiversity have created an urgent need to protect and restore these habitats.

“As well as researching what is happening now and what will likely happen in the future we are also suggesting ways to significantly improve conservation decision-making across the South Atlantic region,” said Baldwin, the Margaret H. Lloyd-Smart State Endowed Chair in the forestry and environmental conservation department at Clemson University. “Habitat connectivity is going to change based on rising sea levels and increased urbanization, the latter of which will shift and move as a result of sea-level rise. So we have two things that are playing major roles in the fragmentation of habitat. But based on our connectivity maps, today’s conservation land trusts and government agencies will be better informed to prioritize ways to create and preserve corridors that will allow animals to move to more optimal habitats as conditions change in the future.”

Continue reading at Clemson University.

High-resolution connectivity maps designed at Clemson University display the potential corridors used by animal populations to move between both large and small areas.

Image Credit: Paul Leonard and Edward Duffy / Clemson University