The billions of single-celled marine organisms known as phytoplankton can drift from one region of the world's oceans to almost any other place on the globe in less than a decade, Princeton University researchers have found.

Unfortunately, the same principle can apply to plastic debris, radioactive particles and virtually any other man-made flotsam and jetsam that litter our seas, the researchers found. Pollution can thus become a problem far from where it originated within just a few years.

The billions of single-celled marine organisms known as phytoplankton can drift from one region of the world's oceans to almost any other place on the globe in less than a decade, Princeton University researchers have found.

Unfortunately, the same principle can apply to plastic debris, radioactive particles and virtually any other man-made flotsam and jetsam that litter our seas, the researchers found. Pollution can thus become a problem far from where it originated within just a few years.

The finding that objects can move around the globe in just 10 years suggests that ocean biodiversity may be more resilient to climate change than previously thought, according to a study published this week in the journal Nature Communications. Phytoplankton form the basis of the marine food chain, and their rapid spread could enable them to quickly repopulate areas where warming seas or ocean acidification have decimated them.

"Our study shows that the ocean is quite efficient in moving things around," said Bror Fredrik Jönsson, an associate research scholar in Princeton's Department of Geosciences, who conducted the study with co-author James R. Watson, a former Princeton postdoctoral researcher who is now a researcher at Stockholm University.

"This comes as a surprise to a lot of people, and in fact we spent about two years confirming this work to make sure we got it right," Jönsson said.

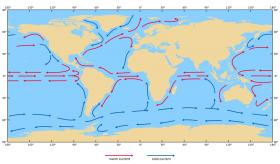

Princeton University researchers found that ocean currents can carry objects to almost any place on the globe in less than a decade, faster than previously thought. The model above shows how phytoplankton traveling on ocean currents would spread over a three-year period. The researchers "released" thousands of particles representing phytoplankton and garbage from a starting point (green) stretching north to south from Greenland to the Antarctic Peninsula. The colors to the left indicate low (blue) or high (red) concentration of particles. Over time, the particles spiral out to reach the North and South Pacific, Europe, Africa and the Indian Ocean. (Animation by Bror Jönsson, Department of Geosciences)

One of the strengths of the model is its approach of following phytoplankton wherever they go throughout the world rather than focusing on their behavior in one region, Jönsson said. Because most marine organisms are mobile, this particle-tracking approach can yield new insights compared to the approach of studying one area of ocean.

The resulting model works for objects that have no ability to control their movement such as phytoplankton, bacteria and man-made debris. Organisms that can control their movement even a small amount — such as zooplankton, which can control their vertical position in water — are not accounted for in the model. Nor does the model apply to objects such as boats that protrude above the water and can be pushed by surface winds.

The team applied a computer algorithm to calculate the fastest route an object can travel via ocean currents between various points on the globe. Most previous studies looked only at movement of phytoplankton within regions. The resulting database, Jönsson said, is analogous to a mileage chart one would find on a roadmap or atlas showing the distance between two cities, except that Jönsson and Watson are indicating the speed of travel between different points.

Continue reading at Princeton University.

Ocean currents image via Shutterstock.