For hundreds of millions of years, Earth's climate has remained on a fairly even keel, with some dramatic exceptions: Around 80 million years ago, the planet's temperature plummeted, along with carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. The Earth eventually recovered, only to swing back into the present-day ice age 50 million years ago.

Now geologists at MIT have identified the likely cause of both ice ages, as well as a natural mechanism for carbon sequestration. Just prior to both periods, massive tectonic collisions took place near the Earth's equator -- a tropical zone where rocks undergo heavy weathering due to frequent rain and other environmental conditions. This weathering involves chemical reactions that absorb a large amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The dramatic drawdown of carbon dioxide cooled the atmosphere, the new study suggests, and set the planet up for two ice ages, 80 million and 50 million years ago.

For hundreds of millions of years, Earth's climate has remained on a fairly even keel, with some dramatic exceptions: Around 80 million years ago, the planet's temperature plummeted, along with carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. The Earth eventually recovered, only to swing back into the present-day ice age 50 million years ago.

Now geologists at MIT have identified the likely cause of both ice ages, as well as a natural mechanism for carbon sequestration. Just prior to both periods, massive tectonic collisions took place near the Earth's equator -- a tropical zone where rocks undergo heavy weathering due to frequent rain and other environmental conditions. This weathering involves chemical reactions that absorb a large amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The dramatic drawdown of carbon dioxide cooled the atmosphere, the new study suggests, and set the planet up for two ice ages, 80 million and 50 million years ago.

"Everybody agrees that on geological timescales over hundreds of millions of years, tectonics control the climate, but we didn't know how to connect this," says Oliver Jagoutz, associate professor of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) at MIT. "I think we're the first ones to really link large-scale tectonic events to climate change."

Jagoutz and his colleagues, EAPS Professor Leigh Royden, and Francis McDonald of Harvard University, have published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Putting the squeeze o

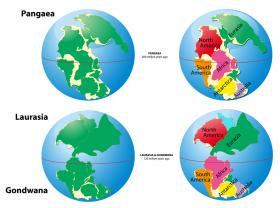

The two tectonic collisions that the team studied stemmed from the same event: the slow northward migration of Gondwana, a supercontinent that spanned the Southern Hemisphere from 300 million to 180 million years ago and eventually broke up to form Antarctica, South America, Africa, India, and Australia.

Around 180 million years ago, tectonic activity began to push fragments of Gondwana up toward the northern supercontinent of Eurasia, which slowly squeezed and eventually closed the Neo-Tethys Ocean, an ancient body of water lying between the supercontinents.

Plate tectonics image via Shutterstock.