Koko the gorilla is best known for a lifelong study to teach her a silent form of communication, American Sign Language. But some of the simple sounds she has learned may change the perception that humans are the only primates with the capacity for speech.

In 2010, Marcus Perlman started research work at The Gorilla Foundation in California, where Koko has spent more than 40 years living immersed with humans — interacting for many hours each day with psychologist Penny Patterson and biologist Ron Cohn.

"I went there with the idea of studying Koko's gestures, but as I got into watching videos of her, I saw her performing all these amazing vocal behaviors," says Perlman, now a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of University of Wisconsin-Madison psychology Professor Gary Lupyan.

Koko the gorilla is best known for a lifelong study to teach her a silent form of communication, American Sign Language. But some of the simple sounds she has learned may change the perception that humans are the only primates with the capacity for speech.

In 2010, Marcus Perlman started research work at The Gorilla Foundation in California, where Koko has spent more than 40 years living immersed with humans — interacting for many hours each day with psychologist Penny Patterson and biologist Ron Cohn.

"I went there with the idea of studying Koko's gestures, but as I got into watching videos of her, I saw her performing all these amazing vocal behaviors," says Perlman, now a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of University of Wisconsin-Madison psychology Professor Gary Lupyan.

The vocal and breathing behaviors Koko had developed were not necessarily supposed to be possible.

"Decades ago, in the 1930s and '40s, a couple of husband-and-wife teams of psychologists tried to raise chimpanzees as much as possible like human children and teach them to speak. Their efforts were deemed a total failure," Perlman says. "Since then, there is an idea that apes are not able to voluntarily control their vocalizations or even their breathing."

Instead, the thinking went, the calls apes make pop out almost reflexively in response to their environment — the appearance of a dangerous snake, for example.

And the particular vocal repertoire of each ape species was thought to be fixed. They didn't really have the ability to learn new vocal and breathing-related behaviors.

These limits fit a theory on the evolution of language, that the human ability to speak is entirely unique among the nonhuman primate species still around today.

"This idea says there's nothing that apes can do that is remotely similar to speech," Perlman says. "And, therefore, speech essentially evolved — completely new — along the human line since our last common ancestor with chimpanzees."

However, in a study published online in July in the journal Animal Cognition, Perlman and collaborator Nathaniel Clark of the University of California, Santa Cruz, sifted 71 hours of video of Koko interacting with Patterson and Cohn and others, and found repeated examples of Koko performing nine different, voluntary behaviors that required control over her vocalization and breathing. These were learned behaviors, not part of the typical gorilla repertoire.

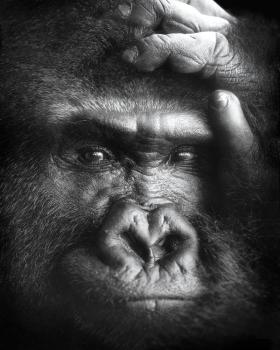

Gorilla image via Shutterstock.

Read more at University of Wisconsin-Madison.