Nobody knows what our skies looked like before fossil fuel burning began; today, about half the cloud droplets in Northern Hemisphere skies formed around particles of pollution. Cloudy skies help regulate our planet’s climate and yet the answers to many fundamental questions about cloud formation remain hazy.

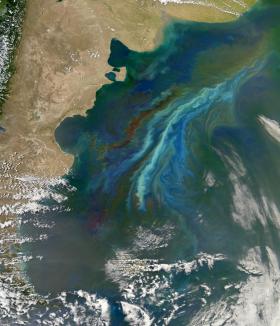

Satellites use chlorophyll’s green color to detect biological activity in the oceans. The lighter-green swirls are a massive December 2010 plankton bloom following ocean currents off Patagonia, at the southern tip of South America.NASA

Nobody knows what our skies looked like before fossil fuel burning began; today, about half the cloud droplets in Northern Hemisphere skies formed around particles of pollution. Cloudy skies help regulate our planet’s climate and yet the answers to many fundamental questions about cloud formation remain hazy.

Satellites use chlorophyll’s green color to detect biological activity in the oceans. The lighter-green swirls are a massive December 2010 plankton bloom following ocean currents off Patagonia, at the southern tip of South America.NASA

New research led by the University of Washington and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory suggest tiny ocean life in vast stretches of the Southern Ocean play a significant role in generating brighter clouds overhead. The results were published July 17 in the online, open-access journal Science Advances.

The study shows that plankton, the tiny drifting organisms in the sea, produce airborne gases and organic matter to seed cloud droplets, which lead to brighter clouds that reflect more sunlight.

“The clouds over the Southern Ocean reflect significantly more sunlight in the summertime than they would without these huge plankton blooms,” said co-lead author Daniel McCoy, a UW doctoral student in atmospheric sciences. “In the summer, we get about double the concentration of cloud droplets as we would if it were a biologically dead ocean.”

Read more at Universtity of Washington.