Temple University researchers have assembled the largest and most accurate tree of life calibrated to time, and surprisingly, it reveals that life has been expanding at a constant rate.

"The constant rate of diversification that we have found indicates that the ecological niches of life are not being filled up and saturated," said Temple professor S. Blair Hedges, a member of the research team's study, published in the early online edition of the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution. "This is contrary to the popular alternative model which predicts a slowing down of diversification as niches fill up with species."

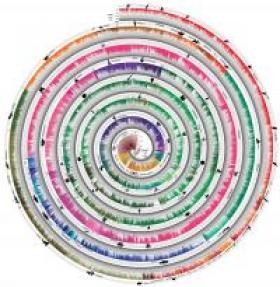

The tree of life compiled by the Temple team is depicted in a new way --- a cosmologically-inspired galaxy of life view --- and contains more than 50,000 species in a tapestry spiraling out from the origin of life.

Temple University researchers have assembled the largest and most accurate tree of life calibrated to time, and surprisingly, it reveals that life has been expanding at a constant rate.

"The constant rate of diversification that we have found indicates that the ecological niches of life are not being filled up and saturated," said Temple professor S. Blair Hedges, a member of the research team's study, published in the early online edition of the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution. "This is contrary to the popular alternative model which predicts a slowing down of diversification as niches fill up with species."

The tree of life compiled by the Temple team is depicted in a new way --- a cosmologically-inspired galaxy of life view --- and contains more than 50,000 species in a tapestry spiraling out from the origin of life.

For the massive meta-study effort, researchers painstakingly assembled data from 2,274 molecular studies, with 96 percent published in the last decade. They built new computer algorithms and tools to synthesize this largest collection of evolutionary peer-reviewed species diversity timelines published to date to produce this Time Tree of Life.

The study also challenges the conventional view of adaptation being the principal force driving species diversification, but rather, underscores the importance of random genetic events and geographic isolation in speciation, taking about 2 million years on average for a new species to emerge onto the scene.

"This finding shows that speciation is more clock-like than people have thought," said Hedges. "Taken together, this indicates that speciation and diversification are separate processes from adaptation, responding more to isolation and time. Adaptation is definitely occurring, so this does not disagree with Darwinism. But it goes against the popular idea that adaptation drives speciation, and against the related concept of punctuated equilibrium which associates adaptive change with speciation."

Image of the new view of the tree of life credit Temple University.

Read more at EurekAlert.