Current levels of greenhouse gas emissions are putting nearly half of California’s natural vegetation at risk from climate stress, with transformative implications for the state’s landscape and the people and animals that depend on it, according to a study led by the University of California, Davis. However, cutting emissions so that global temperatures increase by no more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.2 degrees Fahrenheit) could reduce those impacts by half, with about a quarter of the state’s natural vegetation affected.

Current levels of greenhouse gas emissions are putting nearly half of California’s natural vegetation at risk from climate stress, with transformative implications for the state’s landscape and the people and animals that depend on it, according to a study led by the University of California, Davis. However, cutting emissions so that global temperatures increase by no more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.2 degrees Fahrenheit) could reduce those impacts by half, with about a quarter of the state’s natural vegetation affected.

The study, published in the journal Ecosphere, asks: What are the implications for the state’s vegetation under a business-as-usual emissions strategy, where temperatures increase up to 4.5 degrees Celsius by 2100, compared to meeting targets outlined in the Paris climate agreement that limit warming to 2 degrees Celsius?

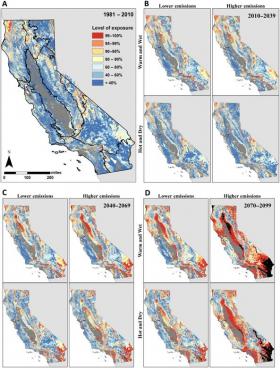

“At current rates of emissions, about 45-56 percent of all the natural vegetation in the state is at risk, or from 61,190 to 75,866 square miles,” said lead author James Thorne, a research scientist with the Department of Environmental Science and Policy at UC Davis. “If we reduce the rate to Paris accord targets, those numbers are lowered to between 21 and 28 percent of the lands at climatic risk.”

The report notes that this is a conservative estimate because it only examines direct climate exposure. It does not include increased wildfire or insect attacks on forests, which are also intensifying and likely to increase with further warming. These secondary effects are likely to have large impacts, as well, the authors say. For example, during the recent drought, more than 127 million trees died primarily due to beetle outbreaks, and wildfires have consumed extensive amounts of natural vegetation.

Read more at University of California - Davis

Image: The climate exposure of 30 California vegetation types under the current time (A) and three future periods: (B) 2011-2039, (C) 2040-2069, and (D) 2070-2099. Red and orange areas above 95 percent are most at risk. Blue areas less than 80 percent exposed are considered climatically suitable. "Lower emissions" are in line with Paris agreement targets; "higher emissions" represent current, business-as-usual trajectories. (Credit: UC Davis)