The first images from the Solar Ultraviolet Imager or SUVI instrument aboard NOAA’s GOES-16 satellite have been successful, capturing a large coronal hole on Jan. 29, 2017.

The sun’s 11-year activity cycle is currently approaching solar minimum, and during this time powerful solar flares become scarce and coronal holes become the primary space weather phenomena – this one in particular initiated aurora throughout the polar regions. Coronal holes are areas where the sun's corona appears darker because the plasma has high-speed streams open to interplanetary space, resulting in a cooler and lower-density area as compared to its surroundings.

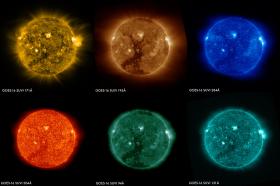

The first images from the Solar Ultraviolet Imager or SUVI instrument aboard NOAA’s GOES-16 satellite have been successful, capturing a large coronal hole on Jan. 29, 2017.

The sun’s 11-year activity cycle is currently approaching solar minimum, and during this time powerful solar flares become scarce and coronal holes become the primary space weather phenomena – this one in particular initiated aurora throughout the polar regions. Coronal holes are areas where the sun's corona appears darker because the plasma has high-speed streams open to interplanetary space, resulting in a cooler and lower-density area as compared to its surroundings.

SUVI is a telescope that monitors the sun in the extreme ultraviolet wavelength range. SUVI will capture full-disk solar images around-the-clock and will be able to see more of the environment around the sun than earlier NOAA geostationary satellites.

The sun’s upper atmosphere, or solar corona, consists of extremely hot plasma, an ionized gas. This plasma interacts with the sun’s powerful magnetic field, generating bright loops of material that can be heated to millions of degrees. Outside hot coronal loops, there are cool, dark regions called filaments, which can erupt and become a key source of space weather when the sun is active. Other dark regions are called coronal holes, which occur where the sun’s magnetic field allows plasma to stream away from the sun at high speed. The effects linked to coronal holes are generally milder than those of coronal mass ejections, but when the outflow of solar particles is intense – can pose risks to satellites in Earth orbit.

Read more at NASA / Goddard Space Flight Center

Image: These images of the sun were captured at the same time on January 29, 2017 by the six channels on the SUVI instrument on board GOES-16 and show a large coronal hole in the sun’s southern hemisphere. Each channel observes the sun at a different wavelength, allowing scientists to detect a wide range of solar phenomena important for space weather forecasting.

Credits: NOAA