Mars is blanketed by a thin, mostly carbon dioxide atmosphere -- one that is far too thin to keep water from freezing or quickly evaporating. However, geological evidence has led scientists to conclude that ancient Mars was once a warmer, wetter place than it is today. To produce a more temperate climate, several researchers have suggested that the planet was once shrouded in a much thicker carbon dioxide atmosphere. For decades that left the question, "Where did all the carbon go?"

The solar wind stripped away much of Mars' ancient atmosphere and is still removing tons of it every day. But scientists have been puzzled by why they haven't found more carbon -- in the form of carbonate -- captured into Martian rocks. They have also sought to explain the ratio of heavier and lighter carbons in the modern Martian atmosphere.

Mars is blanketed by a thin, mostly carbon dioxide atmosphere -- one that is far too thin to keep water from freezing or quickly evaporating. However, geological evidence has led scientists to conclude that ancient Mars was once a warmer, wetter place than it is today. To produce a more temperate climate, several researchers have suggested that the planet was once shrouded in a much thicker carbon dioxide atmosphere. For decades that left the question, "Where did all the carbon go?"

The solar wind stripped away much of Mars' ancient atmosphere and is still removing tons of it every day. But scientists have been puzzled by why they haven't found more carbon -- in the form of carbonate -- captured into Martian rocks. They have also sought to explain the ratio of heavier and lighter carbons in the modern Martian atmosphere.

Now a team of scientists from the California Institute of Technology and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, both in Pasadena, offer an explanation of the "missing" carbon, in a paper published today by the journal Nature Communications.

They suggest that 3.8 billion years ago, Mars might have had a moderately dense atmosphere. Such an atmosphere -- with a surface pressure equal to or less than that found on Earth -- could have evolved into the current thin one, not only minus the "missing" carbon problem, but also in a way consistent with the observed ratio of carbon-13 to carbon-12, which differ only by how many neutrons are in each nucleus.

"Our paper shows that transitioning from a moderately dense atmosphere to the current thin one is entirely possible," says Caltech postdoctoral fellow Renyu Hu, the lead author. "It is exciting that what we know about the Martian atmosphere can now be pieced together into a consistent picture of its evolution -- and this does not require a massive undetected carbon reservoir."

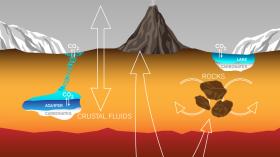

When considering how the early Martian atmosphere might have transitioned to its current state, there are two possible mechanisms for the removal of the excess carbon dioxide. Either the carbon dioxide was incorporated into minerals in rocks called carbonates or it was lost to space.

An August 2015 study used data from several Mars-orbiting spacecraft to inventory carbonates, showing there are nowhere near enough in the upper half mile (one kilometer) or the crust to contain the missing carbon from a thick early atmosphere during a time when networks of ancient river channels were active, about 3.8 billion years ago.

The escaped-to-space scenario has also been problematic. Because various processes can change the relative amounts of carbon-13 to carbon-12 isotopes in the atmosphere, "we can use these measurements of the ratio at different points in time as a fingerprint to infer exactly what happened to the Martian atmosphere in the past," says Hu. The first constraint is set by measurements of the ratio in meteorites that contain gases released volcanically from deep inside Mars, providing insight into the starting isotopic ratio of the original Martian atmosphere. The modern ratio comes from measurements by the SAM (Sample Analysis at Mars) instrument on NASA's Curiosity rover.

This graphic depicts paths by which carbon has been exchanged among Martian interior, surface rocks, polar caps, waters and atmosphere, and also depicts a mechanism by which it is lost from the atmosphere with a strong effect on isotope ratio. Image Credit: Lance Hayashida/Caltech via NASA.

Read more at JPL NASA.