A new explanation for a type of order, or symmetry, in an exotic material made with uranium may lead to enhanced computer displays and data storage systems, and more powerful superconducting magnets for medical imaging and levitating high-speed trains, according to a Rutgers-led team of research physicists.

The team’s findings are a major step toward explaining a puzzle that physicists worldwide have been struggling with for 30 years, when scientists first noticed a change in the material’s electrical and magnetic properties but were unable to describe it fully. This subtle change occurs when the material is cooled to 17.5 degrees above absolute zero or lower (a bone-chilling minus 428 degrees Fahrenheit).

A new explanation for a type of order, or symmetry, in an exotic material made with uranium may lead to enhanced computer displays and data storage systems, and more powerful superconducting magnets for medical imaging and levitating high-speed trains, according to a Rutgers-led team of research physicists.

The team’s findings are a major step toward explaining a puzzle that physicists worldwide have been struggling with for 30 years, when scientists first noticed a change in the material’s electrical and magnetic properties but were unable to describe it fully. This subtle change occurs when the material is cooled to 17.5 degrees above absolute zero or lower (a bone-chilling minus 428 degrees Fahrenheit).

“This ‘hidden order’ has been the subject of nearly a thousand scientific papers since it was first reported in 1985 at Leiden University in the Netherlands,” said Girsh Blumberg, professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the School of Arts and Sciences.

Collaborators from Rutgers University, the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, and Leiden University published their findings this week in the web-based journal Science Express, which features selected research papers in advance of their appearance in the journal Science. Blumberg and two Rutgers colleagues, graduate student Hsiang-Hsi Kung and professor Kristjan Haule, led the collaboration.

Changes in order are what make liquid crystals, magnetic materials and superconductors work and perform useful functions. While the Rutgers-led discovery won’t transform high-tech products overnight, this kind of knowledge is vital to ongoing advances in electronic technology.

“The Los Alamos collaborators produced a crystalline sample of the uranium, ruthenium and silicon compound with unprecedented purity, a breakthrough we needed to make progress in solving the puzzle of hidden order,” said Blumberg. Uranium is commonly known as an element in nuclear reactor fuel or weapons material, but in this case, physicists value it as a heavy metal with electrons that behave differently than those in common metals.

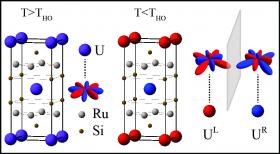

Below the hidden order temperature of 17.5 degrees Kelvin, uranium electron orbital patterns in adjacent crystal layers become mirror images of each other (right side of illustration). Above that temperature, uranium electron orbitals are the same (left side of illustration).

Image credit: Hsiang-Hsi Kung

Read more at Rutgers University.