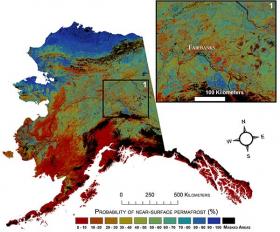

Using statistically modeled maps drawn from satellite data and other sources, U.S. Geological Survey scientists have projected that the near-surface permafrost that presently underlies 38 percent of boreal and arctic Alaska would be reduced by 16 to 24 percent by the end of the 21st century under widely accepted climate scenarios. Permafrost declines are more likely in central Alaska than northern Alaska.

Northern latitude tundra and boreal forests are experiencing an accelerated warming trend that is greater than in other parts of the world. This warming trend degrades permafrost, defined as ground that stays below freezing for at least two consecutive years. Some of the adverse impacts of melting permafrost are changing pathways of ground and surface water, interruptions of regional transportation, and the release to the atmosphere of previously stored carbon.