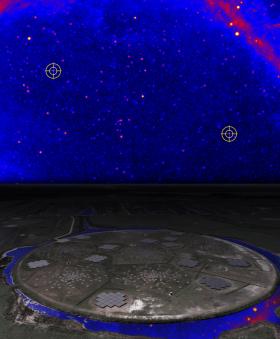

By following up on mysterious high-energy sources mapped out by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, the Netherlands-based Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) radio telescope has identified a pulsar spinning at more than 42,000 revolutions per minute, making it the second-fastest known.

articles

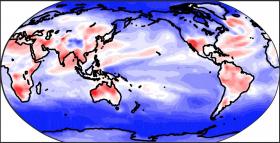

Warmer World May Bring More Local, Less Global, Temperature Variability

Many tropical or subtropical regions could see sharp increases in natural temperature variability as Earth’s climate warms over coming decades, a new Duke University-led study suggests.

Medical camera sees through the body

Scientists have developed a camera that can see through the human body.

The camera is designed to help doctors track medical tools known as endoscopes that are used to investigate a range of internal conditions.

Eat Fat, Live Longer?

As more people live into their 80s and 90s, researchers have delved into the issues of health and quality of life during aging. A recent mouse study at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine sheds light on those questions by demonstrating that a high-fat, or ketogenic, diet not only increases longevity, but improves physical strength.

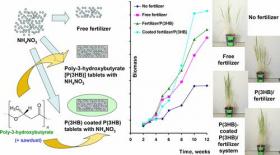

Scientists developed "smart fertilizer"

According to the head of the works Tatiana Volova, Professor of SibFU and the Head of Laboratory in the Institute of Biophysics KSC of SB RAS, development of a new generation of drugs with the use of bio-decomposable materials which decompose under the influence of the microflora to innocuous products and provide a gradual release of the active principle into the soil, is the newest area of research in the field of agriculture. For example, nitrogen is one of the elements, which is often lacking for the growth and development of plants. Plant-available nitrogen in the soil is usually small. Moreover, its compounds are chemically very mobile and easily leached from the soil. In this connection there is the task of developing such forms of nitrogen fertilizers that provide slow release nitrogen and the constancy of its concentration in the soil.

When strangers can control our lights

Smart home products such as lamps controlled via mobile devices are becoming ever more popular in private households. We would, however, feel vulnerable in our own four walls if strangers suddenly started switching the lights in our homes on and off. Researchers at the IT Security Infrastructures group, FAU have discovered security problems of this nature in smart lights manufactured by GE, IKEA, Philips and Osram.