A new methodology developed by the Indian Statistical Institute, and WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society) may revolutionize how to count tigers and other big cats over large landscapes.

articles

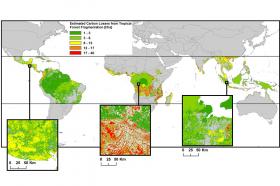

Emissions from the edge of the forest

When talk is of important ecosystems, tropical forests are top of the list. After all, half of the carbon stored in all of the Earth's vegetation is contained in these ecosystems. Deforestation has a correspondingly fatal effect. Scientists estimate that this releases 1000 million tonnes of carbon every year, which, in the form of greenhouse gasses, drives up global temperatures. That is not all, however, reveals a new study by the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) and the University of Maryland. A team of scientists has discovered that fragmentation of formerly contiguous areas of forest leads to carbon emissions rising by another third. Researchers emphasise in the scientific journal Nature Communications that this previously neglected effect should be taken into account in future IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) reports.

Tackling resilience: Finding order in chaos to help buffer against climate change

"Resilience" is a buzzword often used in scientific literature to describe how animals, plants and landscapes can persist under climate change. It’s typically considered a good quality, suggesting that those with resilience can withstand or adapt as the climate continues to change.

But when it comes to actually figuring out what makes a species or an entire ecosystem resilient ― and how to promote that through restoration or management ― there is a lack of consensus in the scientific community.

USGS and Partners Team Up to Track Down Nonnative and Invasive Fishes in South Florida

U.S. Geological Survey scientists teamed up with government, nonprofit, and university partners in South Florida's Big Cypress National Preserve to hold a scientific scavenger hunt for nonnative and invasive freshwater fish species.

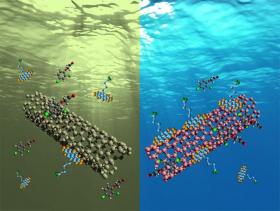

Reusable carbon nanotubes could be the water filter of the future, says RIT study

A new class of carbon nanotubes could be the next-generation clean-up crew for toxic sludge and contaminated water, say researchers at Rochester Institute of Technology.

Enhanced single-walled carbon nanotubes offer a more effective and sustainable approach to water treatment and remediation than the standard industry materials—silicon gels and activated carbon—according to a paper published in the March issue of Environmental Science Water: Research and Technology.

A superbloom of wildflowers overtakes California's southeastern deserts in March 2017

After five years of exceptional drought, desert landscapes across southern California exploded with “superblooms” of wildflowers this March following ample winter precipitation. According to local news reports, it’s the most spectacular display some locations have seen in more than two decades.