Drought-stricken areas anxiously await the arrival of rain. Full recovery of the ecosystem, however, can extend long past the first rain drops on thirsty ground.

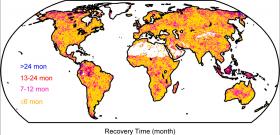

According to a study published August 10 in Nature, the length of drought recovery depends on several factors, including the region of the world and the post-drought weather conditions. The authors, including William Anderegg of the University of Utah, warn that more frequent droughts in the future may not allow time for ecosystems to fully recover before the next drought hits.

Find a video abstract of this study here. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and by NASA.