After long-awaited snowfall in January, parts of the Alps are now covered with fresh powder and happy skiers. But the Swiss side of the iconic mountain range had the driest December since record-keeping began over 150 years ago, and 2016 was the third year in a row with scarce snow over the Christmas period. A study published today in The Cryosphere, a journal of the European Geosciences Union, shows bare Alpine slopes could be a much more common sight in the future.

articles

Antarctic sea ice extent lowest on record

This year the extent of summer sea ice in the Antarctic is the lowest on record. The Antarctic sea ice minimum marks the day – typically towards end of February – when sea ice reaches its smallest extent at the end of the summer melt season, before expanding again as the winter sets in.

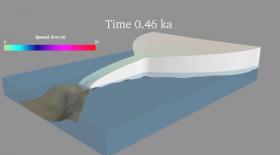

How an Ice Age paradox could inform sea level rise predictions

New findings from the University of Michigan explain an Ice Age paradox and add to the mounting evidence that climate change could bring higher seas than most models predict.

The study, published in Nature, shows how small spikes in the temperature of the ocean, rather than the air, likely drove the rapid disintegration cycles of the expansive ice sheet that once covered much of North America.

Method to predict surface ozone pollution levels provides 48-hour heads-up

A novel air quality model will help air quality forecasters predict surface ozone levels up to 48-hours in advance and with fewer resources, according to a team of meteorologists.

The method, called regression in self-organizing map (REGiS), weighs and combines statistical air quality models by pairing them with predicted weather patterns to create probabilistic ozone forecasts. Unlike current chemical transport models, REGiS can predict ozone levels up to 48 hours in advance without requiring significant computational power.

Crystal Growth, Earth Science and Tech Demo Research Launching to Orbiting Laboratory

The tenth SpaceX cargo resupply launch to the International Space Station, targeted for launch Feb. 18, will deliver investigations that study human health, Earth science and weather patterns. Here are some highlights of the research headed to the orbiting laboratory:

Crystal growth investigation could improve drug delivery, manufacturing

Monoclonal antibodies are important for fighting off a wide range of human diseases, including cancers. These antibodies work with the natural immune system to bind to certain molecules to detect, purify and block their growth. The Microgravity Growth of Crystalline Monoclonal Antibodies for Pharmaceutical Applications (CASIS PCG 5) investigation will crystallize a human monoclonal antibody, developed by Merck Research Labs, that is currently undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of immunological disease.

Snow Science in Support of Our Nation's Water Supply

Researchers have completed the first flights of a NASA-led field campaign that is targeting one of the biggest gaps in scientists' understanding of Earth's water resources: snow.

NASA uses the vantage point of space to study all aspects of Earth as an interconnected system. But there remain significant obstacles to measuring accurately how much water is stored across the planet's snow-covered regions. The amount of water in snow plays a major role in water availability for drinking water, agriculture and hydropower.