Inside NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland the James Webb Space Telescope team completed the environmental portion of vibration testing and prepared for the acoustic test on the telescope.

articles

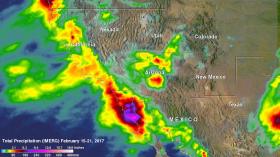

NASA Eyes Pineapple Express Soaking California

NASA has estimated rainfall from the Pineapple Express over the coastal regions southwestern Oregon and northern California from the series of storms in February, 2017.

The West Coast is once again feeling the effects of the "Pineapple Express." Back in early January one of these "atmospheric river" events, which taps into tropical moisture from as far away as the Hawaiian Islands, brought heavy rains from Washington state and Oregon all the way down to southern California. This second time around, many of those same areas were hit again. The current rains are a result of three separate surges of moisture impacting the West Coast. The first such surge in this current event began impacting the Pacific coastal regions of Washington, Oregon, and northern California on February 15.

Melting Sea Ice May Be Speeding Nature's Clock in the Arctic

Spring is coming sooner to some plant species in the low Arctic of Greenland, while other species are delaying their emergence amid warming winters. The changes are associated with diminishing sea ice cover, according to a study published in the journalBiology Letters and led by the University of California, Davis.

The timing of seasonal events, such as first spring growth, flower bud formation and blooming, make up a plant’s phenology — the window of time it has to grow, produce offspring and express its life history. Think of it as “nature’s clock.”

Thinking 'Glocally' About Water Scarcity: Why We Need to Act Now

What if walking three hours to get water was a first-world problem?

Manhattan-Sized Iceberg Breaks Off Antarctica

Antarctica’s Pine Island Glacier lost another large chunk of ice at the end of January. The section of ice that broke off the glacier on the western coast of Antarctica was roughly the size of Manhattan. It was 10 times smaller than the piece the same glacier sloughed in July 2015.

Cosmic blast from the past

Three decades ago, a massive stellar explosion sent shockwaves not only through space but also through the astronomical community. SN 1987A was the closest observed supernova to Earth since the invention of the telescope and has become by far the best studied of all time, revolutionising our understanding of the explosive death of massive stars.