Kara Mertz tries to run an eco-conscious home. She buys wind energy credits to offset her electricity usage, and she owns a solar water heater. But her carbon footprint is still significant, thanks in part to the 20 gadgets her teenage son is constantly recharging. Fortunately for Mertz, her hometown of Boulder, Colorado, may soon have options that allow far greater control over energy use.

Kara Mertz tries to run an eco-conscious home. She buys wind energy credits to offset her electricity usage, and she owns a solar water heater. But her carbon footprint is still significant, thanks in part to the 20 gadgets her teenage son is constantly recharging.

Fortunately for Mertz, her hometown of Boulder, Colorado, may soon have options that allow far greater control over energy use. Last month, power company Xcel Energy selected Boulder to become the world's first "Smart Grid City," an experiment in one of the latest efficiency technologies. If the new system generates enough savings to rationalize the high implementation cost, a revolution of energy-efficient power grids and improved renewable energy use may sweep the world.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

"How much of [my son's electronics] are sucking off the grid and we don't realize it?" said Mertz, who serves as assistant to the city manager. "If all of a sudden we look at where money is going, it's very enlightening."

Grid of the Future

Smart grids rely on advanced metering systems to form a direct connection between residents and power companies. Based on a home's average electricity use, the meters calculate the next day's expected electric bill, identify how much power various appliances require, and provide homeowners with options to reduce their energy costs. The homeowner can then, for example, turn off the pool heater when electricity is most expensive, or use air conditioning when electricity is cheapest-making it possible to coast through the "peak" hours of high electricity demand.

The advanced meters also tell utility companies as soon as a power outage occurs. This instantaneous information allows the utility to address problems faster and prevent massive blackouts by rerouting electricity around the grid's troubled areas.

"One aspect [of a smart grid] is that it can help promote energy efficiency; another is it can help improve reliability...it's multi-dimensional," said Don Von Dollen, a smart grid program manager at the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) in Palo Alto, California. EPRI estimates that power outages and power quality disturbances alone cost U.S. businesses more than $120 billion a year.

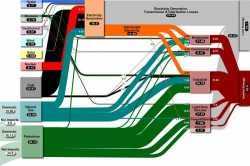

The "grid of the future" may also fuel an increase in renewable energy demand. Currently, wind turbines or solar panels generally feed into the grid only when the wind blows or the sun shines. But with smart grids, a utility may be able to "turn off" natural gas or coal-fired power plants at times when renewably sourced energy is available-and re-route the power, Von Dollen explained. This is much more efficient for the power companies, he said.

For years, energy-efficiency education campaigns have struggled to motivate widespread reductions in energy use. Smart grids, in contrast, offer a way for consumers to directly realize the economic benefits of efficiency, potentially spurring greater action. To research the effects of smart grids on consumer purchasing behavior and energy use, Xcel Energy will collaborate with the University of Colorado at Boulder. "It's a case study of such an important environmental aspect," said Alison Peters, managing director of the university's Deming Center for Entrepreneurship.

The Challenge Ahead

Minnesota-based Xcel Energy selected Boulder for its pilot initiative due to the town's geographic isolation, population size, and technologically savvy and environmentally conscious residents. In recent years, Boulder has ratified the Kyoto Protocol, passed America's first city-wide carbon tax, and even purchased the URL http://www.environmentalaffairs.com/ to link to the municipality's Web site.

City officials are hoping the Smart Grid project will help Boulder meet its carbon-cutting goals. The city's 2006 greenhouse gas emissions inventory showed an increase in emissions over 2005, with as much as 61 percent of the total coming from electricity generation. "We love being the guinea pig," Mertz said. "There's a critical mass of people in this community who are interested in how they're using their energy."

Xcel's $100 million experiment in Boulder is the first city-wide showcase of the various smart grid technologies now available. In California and Texas, power companies are installing certain elements of smart grid technologies, such as updating millions of meters. Both states forced the changes and are compensating utilities for some of the immediate costs. The price of converting only portions of California residents' meters is estimated at $3 billion.

"Just changing millions of meters is a huge job," said Tom Nelson with the National Institute of Standards and Technology, who standardizes electricity meters. "It's not just changing out the meter. They have to communicate which meter is at which house for the billing department."

Other U.S. states and some parts of Europe are also developing smart grids. "A lot of other states are watching what goes on in Texas and California to see if they should follow them or learn from them," Von Dollen said. "There's a greater urgency within Europe than there is in the U.S. But as far as deployments, the U.S. is a little farther ahead."

According to Kurt Yeager, director of the Galvin Electricity Initiative, a campaign to improve the U.S. grid system, despite incentives provided in the recent energy bill, more government involvement is needed at the federal level. "The biggest impediment to the smart electric grid transition is neither technical nor economic," Yeager told a Congressional committee last year. "Instead, the transition is limited today by obsolete regulatory barriers and disincentives that echo from an earlier era."

In 2007, carbon dioxide emissions from U.S. power plants jumped 2.9 percent, the greatest single-year increase since 1988. They have risen 11.7 percent since 1997 as the demand for electricity continues to rise, according to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data.