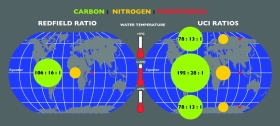

The Redfield ratio has been a fundamental feature in understanding the biogeochemical cycles of the oceans and has been used since 1934 when oceanographer Alfred Redfield found that the elemental composition of marine organic matter is constant across all regions. By analyzing samples of marine biomass, Redfield found that the stoichiometric ratios of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus remain consistent with a ratio of 106:16:1 in ocean regions. However, according to new work by UC Irvine and other researchers, models of carbon dioxide in the world's oceans need to be revised.

The Redfield ratio has been a fundamental feature in understanding the biogeochemical cycles of the oceans and has been used since 1934 when oceanographer Alfred Redfield found that the elemental composition of marine organic matter is constant across all regions. By analyzing samples of marine biomass, Redfield found that the stoichiometric ratios of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus remain consistent with a ratio of 106:16:1 in ocean regions.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

However, according to new work by UC Irvine and other scientists, models of carbon dioxide in the world's oceans need to be revised.

As global marine temperatures have fluctuated trillions of plankton near the surface of warm waters have been found to be more carbon-rich than previously thought. Rising temperatures could mean that tiny Prochlorococcus and other microbes digest double the carbon previously calculated.

As a result of these findings, the researchers have upset the Redfield ratio as the study's authors have found dramatically different ratios at a variety of marine locations in which latitude plays the biggest role in disrupting the ratio.

For example, the researchers detected far higher levels of carbon in warm, nutrient-starved areas (195:28:1) near the equator than in cold, nutrient-rich polar zones (78:13:1).

"The Redfield concept remains a central tenet in ocean biology and chemistry. However, we clearly show that the nutrient content ratio in plankton is not constant and thus reject this longstanding central theory for ocean science," said lead author Adam Martiny, associate professor of Earth system science and ecology & evolutionary biology at UC Irvine. "Instead, we show that plankton follow a strong latitudinal pattern."

He and fellow investigators made several expeditions to gather water samples from places like the Bering Sea, the North Atlantic near Denmark, and the Caribbean to name a few.

They used a sophisticated cell sorter aboard the research vessel to analyze samples at the molecular level. They also compared their data to published results from 18 other marine voyages.

Martiny noted that since Redfield first announced his findings, "there have been people over time putting out a flag, saying, 'Hey, wait a minute.'" But for the most part, Redfield's ratio of constant elements is a staple of textbooks and research. In recent years, Martiny said, "a couple of models have suggested otherwise, but they were purely models. This is really the first time it's been shown with observation. That's why it's so important."

The study was published online Sunday in Nature Geoscience.

Read more at the University of California, Irvine.

Map graphic courtesy of UC Irvine.