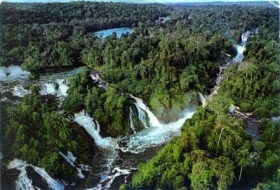

While we have fixated on our little local worries over the past week, the biggest news story of the year passed unnoticed in the night. The Brazilian government was forced to admit that the destruction of the Amazon rainforest has returned to ecocidal levels. An area the size of Belgium, taking thousands of years to evolve, was destroyed in the past year alone. Some 20 per cent of the forest has now been trashed, with a further 40 per cent set to be slashed in my lifetime. This is steadily happening to all the rainforests on earth.

While we have fixated on our little local worries over the past week, the biggest news story of the year passed unnoticed in the night. The Brazilian government was forced to admit that the destruction of the Amazon rainforest has returned to ecocidal levels. An area the size of Belgium, taking thousands of years to evolve, was destroyed in the past year alone. Some 20 per cent of the forest has now been trashed, with a further 40 per cent set to be slashed in my lifetime. This is steadily happening to all the rainforests on earth.

Long after we have forgotten who won the Florida primary or precisely why Peter Hain resigned from the Cabinet, people will be living with the consequences of this news.

The rainforests  with the Amazon by far the largest  are the planet's air conditioner. They suck up millions of tons of greenhouse gases and store them safely out of the atmosphere. But as we hack them down, they are releasing these warming gases. Soon, we will reach a point where there is so much carbon in the atmosphere that the system will pack in and stop extracting anything at all.

We will all feel the heat. It is a stark scientific fact that the last time the world warmed by 6C  the upper-end of the UN scientists' predictions for this century  so quickly, almost everything on Earth died.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

Comforting though it would be, this is not a story about Those Incompetent Foreigners, unable to look after the world's forests. The destruction of the Amazon is currently being pushed and promoted by you and me, through both our consumer choices and our tax money.

The fragile Amazon ecosystem is trapped today in a pincer movement: it is simultaneously being cut down and heated up. Let's start with the cutting, which has been so severe this winter that Gilberto Câmara, head of Brazil's National Institute for Space Research, said: "We had never seen this before in Amazonia." Logging by vast agribusinesses has increased to clear space to produce products for Europe and the US. The biggest slash-and-burn growth industry in Amazonia today is soy production  half of which is then shipped to Europe to feed the animals we are going to milk and eat. A Greenpeace study found that Amazonian soy is in every part of the British food chain, with no major supplier weeding it out. So when you eat a burger, chances are you are effectively eating part of the Amazon.

Logging is also carried out for a range of other rich-world wants. There are currently no legal restrictions in Britain or the US on selling illegal timber pillaged from the Amazon. The craze for biofuels is also (ironically) leading to the burning to rainforest to make way for sugar cane plantations.

And logging doesn't only trash the trees it chops down and ships off; it also makes the trees it leaves behind much more vulnerable to fire. Until a few decades ago, scientists thought it was impossible for such humid tropical rainforests to burn. But it turns out chopping down trees breaks the dense carapace of leaves that covers the forest, allowing sunlight to break through. This dries out the leaf litter that lies on the floor  turning it into tinder. In a major study of the 1983 Borneo fires, it was found that "forests that had been logged were the ones that burned; unlogged forests resisted fire".

These slashed-back forests are then being exposed to unnaturally high temperatures, caused by man-made global warming. (That's you and me again.) In 2005, the Amazon suffered one of the worst droughts in its modern history, and 2007 was almost as bad. Natural variation suggests the Amazon should have serious drought-led fires at 400- to 700-year intervals, but today, they are happening every five to 15 years. It's a vicious cycle: cutting back the forests causes more global warming, which then burns up more forests, which causes more global warming, which burns up the forests even more, and on and on.

The scale of all this is sometimes hard to appreciate: deforestation causes more carbon emissions than every train, plane and automobile on earth.

But you and I do not only wreck the rainforests through our purchasing power; our government is also helpfully doing it for us. The British Government is now one of the biggest funders of the World Bank  and its record is plain. In Congo, I saw the second-largest rainforest on earth beginning to be consumed. The logged stumps lay like stubble on a recently-shaved face, and the indigenous pygmies wandered homeless and hopeless.

The World Bank's own leaked internal investigation admitted it had encouraged vast multinational logging companies to move in and cause "irreversible damage". Robert Goodland, who worked in a senior position at the Bank for 23 years, says this is no anomaly. He argues that the destruction of the Amazon has been "aided and encouraged by the Bank", because its focus is "on helping multi-nationals extract oil, gas and other resources from developing countries".

This leaves the British Government in a bizarre situation. With one hand it is sensibly paying the governments of Guyana and Congo not to cut down their rainforests, while with the other hand it is slathering cash on the World Bank to demand it does the opposite.

So how do you and I stop being part of the problem, and become part of the solution? There are some easy personal choices: cut back or cut out meat, check all the timber you buy, don't use biofuels. There are some easy governmental choices too: withhold funds from the World Bank until it radically transforms its environmental approach.

But time is short, so we need a much more ambitious approach than that. Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who controls 60 per cent of the Amazon, has been admirably blunt with the world. He gives us two choices. If you want to prevent us from doing with our rainforests what you did with yours, you need to make it worth Brazil's while: pay us to do it, now. (Oh, and cut your own carbon emissions while you're at it.) Otherwise we may as well get the money from plundering the forest today, before global warming and illegal logging kills it in a generation anyway.