Turn greenhouse gases to stone? Transform them into a treacle-like liquid deep under the seabed? The ideas may sound like far-fetched schemes from an alchemist's notebook but scientists are pursuing them as many countries prepare to bury captured greenhouse gases in coming years as part of the fight against global warming.

By Alister Doyle, Environment Correspondent

OSLO (Reuters) - Turn greenhouse gases to stone? Transform them into a treacle-like liquid deep under the seabed?

The ideas may sound like far-fetched schemes from an alchemist's notebook but scientists are pursuing them as many countries prepare to bury captured greenhouse gases in coming years as part of the fight against global warming.

Analysts say the search for a suitable technology could become a $150 billion-plus market. But a big worry is that gases may leak from badly chosen underground sites, perhaps jolted open by an earthquake.

!ADVERTISEMENT!Such leaks could be deadly and would stoke climate change.

Part of the answer could be to petrify or liquefy gases like carbon dioxide -- emitted for example from power plants and factories run on coal, oil or natural gas -- if technical hurdles can be overcome and costs are not too high.

"If you can convert (the gases) to stone, and it's environmentally benign and permanent, then that's better," said Juerg Matter, a German scientist at Columbia University in New York who is working on a project in Iceland to turn carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas, to rock.

In theory, carbon dioxide reacts with porous basalt and turns into a mineral, but no one knows how long that takes. Matter and U.S., French and Icelandic experts plan to inject 50,000 tonnes of the gas into basalt in a test starting in 2009.

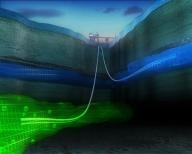

Other researchers say pumping the gas into sediments below the seabed at depths of around 3,000 meters (9,800 ft) would expose it to enough pressure to turn it into a viscous liquid, like honey or treacle.

"High pressure combined with low temperature results in liquid carbon dioxide that can in some cases be denser than sea water," said Kurt Zenz House, of Harvard University.

In the worst known example of a leak, a natural volcanic eruption of carbon dioxide from Lake Nyos in Cameroon in 1986 killed more than 1,700 people. Carbon dioxide is not toxic but can cause asphyxia in high concentrations.

HEATWAVES, STORMS

The U.N. Climate Panel said in a 2005 report that carbon storage could be one of the main ways to offset global warming, which could cause more powerful storms and heatwaves, and melt glaciers from the Himalayas to the Andes.

Carbon capture and storage could keep up to a third of all manmade carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. But no commercial-scale power plant uses the technology yet and a lack of public funding plus legal concerns and safety worries are casting doubts over new projects.

Costs are a big problem: the Climate Panel estimates the penalty for emitting carbon dioxide would have to be stable at $25-$30 a tonne to make carbon storage viable -- pushing up the cost of everything from electricity to steel as the price of slowing climate change.

Carbon emissions' prices in a European Union market of more than 11,000 industrial sites are now above the trigger level, at 24.55 euros ($37.97) a tonne. But the volatile market has often been far below $25 since trading began in 2005.

Most plans by firms such as BP, Rio Tinto, E.ON, American Electric Power and StatoilHydro focus on capturing greenhouse gases and pumping them into porous rocks in shallower oil and gas reservoirs, or into disused mines or saline aquifers.

The longest-running commercial project, stripping carbon dioxide from natural gas at Norway's Sleipner field, began in 1986 and has pumped 10 million tonnes of carbon dioxide into sedimentary rocks about 800 meters (2,625 ft) below the seabed.

"There have been no leaks," said Tore Torp, project leader at operator StatoilHydro. The gas, under pressure, is in a "supercritical" state between liquid and gas and would stay put even in the event of a cataclysmic earthquake, he said.

The project is commercial because Norway, outside the EU, imposed taxes on carbon emissions in 1991. The natural gas at Sleipner has an unusually high percentage of carbon dioxide.

Torp said that the area was far from an earthquake zone.

"In theory, if you had (a giant earthquake) a crack would be filled by the North Sea in seconds and would maintain the pressure down there," Torp said.

"The most important thing for safety is selecting the site. We would avoid the San Andreas fault" in California, he said.

Other similar projects are underway in the United States, Canada and Algeria.

Plans to mix carbon dioxide into the world's oceans, perhaps by dumping thousands of tonnes of iron filings that would encourage the growth of carbon-absorbing algae, are in doubt because of worries they would disrupt marine life.

"All such projects are on hold," said Rene Coenen, office head for the London Convention which oversees dumping at sea. "Our official advice is: 'don't start with it. Wait until we have more knowledge from the scientific side'."

U.S. group Planktos has indefinitely postponed a plan to seed the Pacific Ocean with iron filings. Silicon Valley startup Climos is still studying the idea.

SHELLFISH

Water readily absorbs carbon dioxide -- beer and other fizzy drinks are examples. But carbon makes the seas more acidic and could make it harder for shellfish, corals, crabs or lobsters to build their protective coats.

So carbon burial may be only answer, despite environmentalists' fears that it will encourage nations to keep on burning fossil fuels rather than shift to cleaner renewable energies such as wind or solar power.

"To my mind, if declared safe and acceptable, it is going to be an imperative in terms of an effective solution," said Yvo de Boer, head of the U.N. Climate Change Secretariat.

"If I look at some of the really huge coal-based economies around the world, like China, like India, like South Africa, like Australia, I don't really see how we can come to grips with climate change without using carbon capture and storage."

Costs might be even higher for the more exotic solutions.

In Iceland, the theory goes that a chemical reaction in the calcium- and magnesium-rich basalt formations will bind carbon molecules to form calcite and dolomite. Matter said that costs could be comparable to burial in oil or gas fields.

But it is unclear whether the reactions in the rocks are quick enough. "We do not know if these geochemical reactions ... will take 50, 100 or thousands of years," Matter said.

He said suitable basaltic rocks were also found in places such as India and Siberia.

Kurt Zenz House at Harvard reckoned the costs of pumping carbon to depths of more than 3,000 meters (9,800 ft) would be about 25 percent higher than shallower burial. "It's more expensive but the advantage is that it wouldn't move," he said, adding that it would also not interfere with nature.