Globally, biofuels are being promoted as a kind of nicotine patch to wean the world off its dirty and expensive fossil fuel addiction. Known by some as aboveground oil fields, biodiesel (made from vegetable oils and fats) and ethanol (made by fermenting the sugars in corn and sugarcane) present the opportunity to grow fuel feedstock on agricultural land—plots that can renew every few years rather than every few million. Biofuels lie at the intersection of a myriad of government goals, including energy independence, climate change mitigation, and rural development. Buttressed by 46 national regulatory policies worldwide that support the industry, liquid biofuels provided about three percent of global road transport fuels in 2011, up from two percent in 2009. What is taking place is essentially an agro-fuel revolution—one that will reverberate across millions of hectares, livelihoods, and lives.

Globally, biofuels are being promoted as a kind of nicotine patch to wean the world off its dirty and expensive fossil fuel addiction. Known by some as aboveground oil fields, biodiesel (made from vegetable oils and fats) and ethanol (made by fermenting the sugars in corn and sugarcane) present the opportunity to grow fuel feedstock on agricultural land—plots that can renew every few years rather than every few million. Biofuels lie at the intersection of a myriad of government goals, including energy independence, climate change mitigation, and rural development. Buttressed by 46 national regulatory policies worldwide that support the industry, liquid biofuels provided about three percent of global road transport fuels in 2011, up from two percent in 2009. What is taking place is essentially an agro-fuel revolution—one that will reverberate across millions of hectares, livelihoods, and lives.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

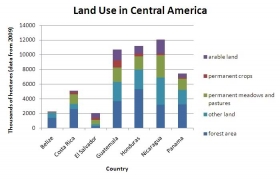

The most straightforward biofuel-promoting policy is a blend mandate: E10 fuel, for instance, delineates a 10 percent ethanol blend. Though Central America has not been at the forefront of biofuel policy until very recently, three countries in the region—Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Panama—now have legally binding biofuel mandates in place, and two more have either targets for the future (Honduras) or blend mandates under review (El Salvador).Though Central American biofuel production is modest compared to other countries in Latin America, these policies will still have significant consequences for land-use change on the isthmus as millions of hectares are set aside for growing sugarcane, African palm, jatropha, castor, and other biofuel feedstocks.

In response to global criticisms that biofuels drive deforestation and threaten food security, Central American governments and interest groups specify that biofuel expansion will occur on “tierras ociosasâ€â€”or vacant, unproductive land. This may include land that was never fit for growing food crops, land heavily grazed by livestock, or land previously deforested. Nicaragua’s Ministry of Energy, for example, claims that 3.2 million hectares have the necessary climate and labor force to cultivate ethanol and biodiesel feedstock. Guatemala’s Renewable Fuels Association identifies an estimated 600,000 hectares of tierras ociosas ideal for growing jatropha without impacting food production. Honduras’s Ministry of Agriculture is promoting African palm plantations on more than 494,000 hectares of abandoned farmland.

For further information see Myth.

Land Use image via World Watch