A new study on how ocean currents transport floating marine debris is helping to explain how garbage patches form in the world’s oceans.

Researchers from the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and colleagues developed a mathematical model that simulates the motion of small spherical objects floating at the ocean surface.

A new study on how ocean currents transport floating marine debris is helping to explain how garbage patches form in the world’s oceans.

Researchers from the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and colleagues developed a mathematical model that simulates the motion of small spherical objects floating at the ocean surface.

The researchers feed the model data on currents and winds to simulate the movement of marine debris. The model’s results were then compared with data from satellite-tracked surface buoys from the NOAA Global Drifter Program’s database. Data from both anchored buoys and those that become unanchored, or undrogued, over time were used to see how each accumulated in the five ocean gyres over a roughly 20-year timeframe.

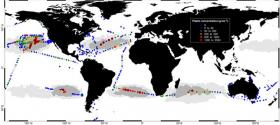

“We found that undrogued drifters accumulate in the centers of the gyres precisely where plastic debris accumulate to form the great garbage patches,” said Francisco Beron-Vera, a research associate professor in the UM Rosenstiel School’s Department of Atmospheric Sciences and lead author of the study. “While anchored drifters, which are designed to closely follow water motion, take a much longer time to accumulate in the center of the gyres.”

The study, which takes into account the combined effects of water and wind-induced drag on these objects, found that the accumulation of marine debris in the subtropical gyres is too fast to be due solely to the effect of trade winds that converge in these regions.

Continue reading at the University of Miami.

Image Credit: Cozar, A., et al. (2014), Plastic debris in the open ocean