A study published by NASA uses satellite remote sensing technology to measure the amount of fluorescent red light emitted by ocean phytoplankton and assess how efficiently the microscopic plants are turning sunlight and nutrients into food through photosynthesis. They can also study how changes in the global environment alter these processes, which are at the center of the ocean food web.

A study published by NASA uses satellite remote sensing technology to measure the amount of fluorescent red light emitted by ocean phytoplankton and assess how efficiently the microscopic plants are turning sunlight and nutrients into food through photosynthesis. They can also study how changes in the global environment alter these processes, which are at the center of the ocean food web.

Researchers have conducted the first global analysis of the health and productivity of ocean plants, as revealed by a unique signal detected by a NASA satellite. Ocean scientists can now remotely measure the amount of fluorescent red light emitted by ocean phytoplankton and assess how efficiently the microscopic plants are turning sunlight and nutrients into food through photosynthesis. They can also study how changes in the global environment alter these processes, which are at the center of the ocean food web.

"This is the first direct measurement of the health of the phytoplankton in the ocean," said Michael Behrenfeld, a biologist who specializes in marine plants at the Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore. "We have an important new tool for observing changes in phytoplankton every week, all over the planet."

The findings were published this month in the journal Biogeosciences and presented at a news briefing on May 28.

The fluorescence data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) gives scientists a tool that enables research to reveal where waters are iron-enriched or iron-limited, and to observe how changes in iron influence plankton. The iron needed for plant growth reaches the sea surface on winds blowing dust from deserts and other arid areas, and from upwelling currents near river plumes and islands.

The new analysis of MODIS data has allowed the research team to detect new regions of the ocean affected by iron deposition and depletion. The Indian Ocean was a particular surprise, as large portions of the ocean were seen to "light up" seasonally with changes in monsoon winds.

Climate change could mean stronger winds pick up more dust and blow it to sea, or less intense winds leaving waters dust-free. Some regions will become drier and others wetter, changing the regions where dusty soils accumulate and get swept up into the air. Phytoplankton will reflect and react to these global changes.

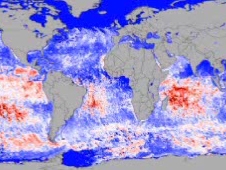

The image shows a data-based map of the "fluorescence yield" of phytoplankton in the oceans during 2004. "Fluorescence yield" is the fraction of absorbed sunlight that is given off by the plants as fluorescence and it changes with the health or stress of the phytoplankton. More fluorescence is emitted when waters are low in key nutrients such as iron. Credit: NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio.

Interestingly, the regions of highest fluorescence yield are almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere. The interactions of Southern Hemisphere and Northern Hemisphere oceanic and atmospheric circulations will be important factors in understanding the significance of these new findings.

For more information: http://www.nasa.gov/topics/earth/features/modis_fluorescence.html