Scientists have discovered a layer of volcanic ash and glass shards in Antarctica, evidence of an old eruption by a still active volcano that researchers believe may be contributing to the thinning of Antarctic glacial ice. Hugh F.J. Corr and David G. Vaughan, two scientists with the British Antarctic Survey, recently published their discovery of the volcanic layer in the journal Nature Geoscience. The discovery is unique according to Dr. Vaughan. He said “This is the first time we have seen a volcano beneath the ice sheet punch a hole through the ice sheet.â€

Scientists have discovered a layer of volcanic ash and glass shards in Antarctica, evidence of an old eruption by a still active volcano that researchers believe may be contributing to the thinning of Antarctic glacial ice.

Hugh F.J. Corr and David G. Vaughan, two scientists with the British Antarctic Survey, recently published their discovery of the volcanic layer in the journal Nature Geoscience. The discovery is unique according to Dr. Vaughan. He said “This is the first time we have seen a volcano beneath the ice sheet punch a hole through the ice sheet.â€

The volcano’s heat could possibly be melting and thinning the ice and raising the speed of the Pine Island Glacier in West Antarctica.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

But while the Pine Island Glacier may be thinning because of the volcano, it’s highly unlikely the thinning of Antarctica’s ice sheet as a whole can be blamed on hidden volcanoes. For one thing, Antarctica has very few active volcanoes. Most glacial scientists, including Dr. Vaughan himself, blame warmer ocean waters for glacial thinning in West Antarctica.

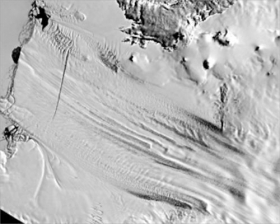

The ash and glass layer the scientists discovered was most likely deposited around the time of Alexander the Great. The eruption would have exploded upwards, pushing through hundreds of metres of ice, spraying ash and volcanic glass shards all over the land surrounding it. Two millennia of snows have covered the volcanic layer, but recent radar surveys found it.

In fact, radar teams discovered the layer in 2004 and 2005, but the reflected radar waves from the layer were so strong they thought it was actual bedrock. A more recent radar survey with improved equipment meant the team discovered the actual bedrock, and thus the layer above it.

The thickness of the ice above the layer mean that the scientists could date it to roughly 200 B.C., plus or minus 240 years or so. But the researchers think they can narrow it down more than that. From previous examinations of ice cores, they knew that a volcano had erupted in Antarctica some time around 325 B.C., although they had not known where the eruption had happened. Dr. Vaughan said: “We’re fairly confident this is the same eruption.â€